A Brief Introduction

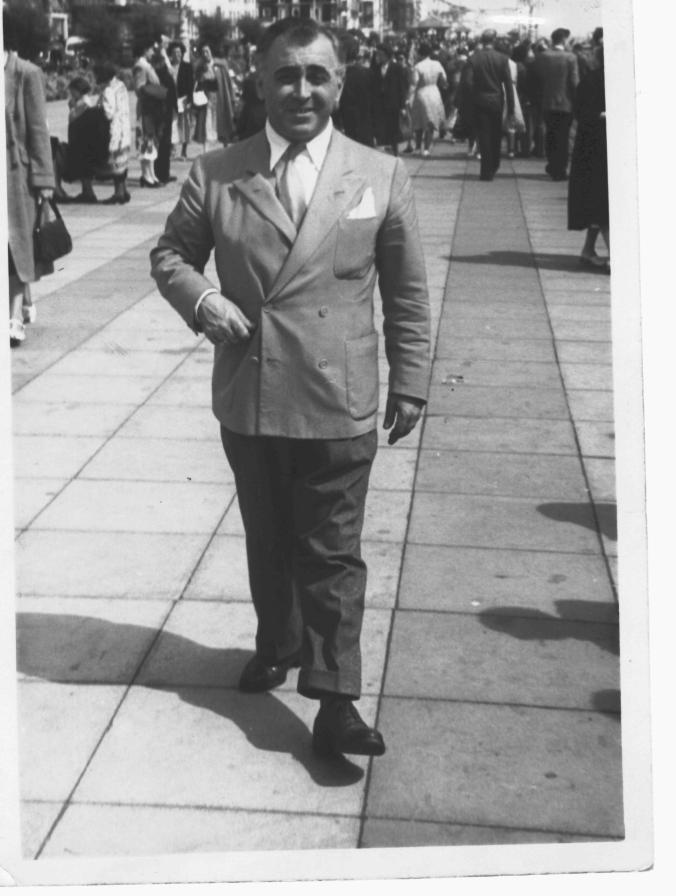

A founding member of the turn-of-the-century group of Yiddish writers who were known as the Absurdelekh, my great-grandfather wrote nearly three hundred short stories and a novel in his lifetime, all under the pen name Talmed Metumtam. He was born in the Mogilev province of what is now Belarus; he died in New York City. To the English-speaking world, he is practically unknown, although his stories have appeared in French, Spanish, German, Latin, Russian and Lithuanian. Talmed Metumtam’s novel, Playing Lefthanded in Toledo, appeared in over fifteen languages and won the Chambermaid Prize in Potsdam – twice.[1] Once in 1929, and again in 1946, after the war, when all the Potsdam laureates gathered at a rebuilt Hall of Culture for a ceremonial re-awarding of the prize in a hopeful gesture towards a new peace. Talmed Metumtam accepted the prize, a silver bust of Epimetheus, the Greek god of Afterthought, in 1929; in 1946, horrified by the war and its inhumanity, he tossed his second prize from the stage, breaking the nose of the Portuguese Minister of Culture in so doing. Talmed Metumtam never won anything else in his life.

[1] Among the many dignitaries gathered in Potsdam on July 8, 1929, for the awarding of the prize were the French Minister of Health, the Soviet Ambassador to England, and Bernadette Schwartz, lady-in-waiting to the Queen of Spain. The following is the text of that speech:

Thank you for the prize. I haven’t been this honored since I received word that I was awarded the Goldene Klyamke award from the Yiddish Writers Association. That was at six this morning, while I was putting on my bowtie for this dinner.

I will begin by saying that writing is a long and dark hallway and writers take many barefoot steps on cold marble but don’t believe those who say that fate is written in ink. There are doors at every stride which are labeled Exit and these doors open into the sky and one who steps out dies quickly, with everlasting purple in his eyes. But I’ve always preferred long suffering over a short jump in the hopes that at the end there will be a beautiful woman who tells me why, for example, some of us implode when still young and clever while others expire unwise and ancient. Since I first took a pen in my left hand at the age of seven I have not dotted one chirek without thinking of Job.

People call me a member of Die Absurdelekh. It’s true, I am a founder and representative of that group. Now I would like to say something about how I got to where I am. Too often people confuse absurdity with idiocy. Absurdity is in the air with our first breath. Idiocy is something we learn, and it can be combated by patience and love. Absurdity is stronger than steel and more dangerous.

I don’t like to talk about grand ideas but if I did I would take an oath that the world is absurd. That the world is being held hostage by a G-d who feels at home on a Mississippi riverboat and a devil who has too much time on his hands. I also would swear that writing solves nothing but it’s a living and who wants to sell fish in the market? This is the guiding premise of Die Absurdelekh. We write the world the way it happens. Which is to say, without justice, without logic, without temperance. And with little or no regard to the true gravity of life and death. We owe this insight to the Old Testament G-d — you know, the one whose chosen people rose and fell as easily in the Five Books of Moses as mankind rose and fell just a decade ago on the bloody pitch of Europe.

My wife Dorah, [It’s not clear why Talmed Metumtam calls his wife Dorah. He married Sarah Yanklevich, his first and only wife, in 1924. Ed.] may she rest in peace, [Also unclear: Sarah accompanied TM to the awards ceremony and died in 1965, outliving her husband by nearly a decade. Ed.] never threw out a thing except her first husband, a man at least two inches shorter than me, and it is to her I owe the fact that my first poem, which I spoke of a minute ago, survives today. It was short, a little nothing, worth about as much as a church bell at a hippodrome but nevertheless I will repeat it here.

The dog eats his breakfast.

Potatoes.

The man eats his breakfast.

Potatoes.

This is a breakfast?

This is a man?

The man is very happy, for a dog.

Even as a little boy, I think I would have been tied to the Absurdelekh. I have spent my whole life trying to find a good reason for why G-d chose Job to torment, if only because I am positive this is an impossible mission. I want the last words on my blue lips to be, “G-d is a spoiled child.” But I also wouldn’t mind, barring that, if I mentioned the dimensions of the holy tabernacle, the death of Moses within view of the Promised Land, Esau’s head rolling into the cave where his father’s body rested, and the binding and unbinding of Isaac. The unbinding is to me even more absurd than the original plan. Human sacrifice we can understand. The forefathers of Israel had no great monopoly on that particular barbarism. But the unbinding of Isaac – how can we keep our faith in a G-d whose scheming is so nefarious? Faith, taken too far, becomes an absurdism.

Let it be noted by the woman in the corner with a notepad scribbling down all the speeches as they’re made, that this is different from denying G-d’s existence. I don’t break bread with apostates and I never will.

Just about ten years ago there was a great war being fought in these lands and I am hopeless that we have truly taken a lesson from it. I return to that accursed favorite book of mine: Once G-d’s little joke was over, after killing all of Job’s children, G-d decided to give back to Job all the property the tormented servant of the Lord had lost, twofold. Then He blessed Job with ten new children. But here it behooves us to pay attention. Even the Almighty couldn’t raise the dead: He replaced Job’s children; He did not resurrect them. We should keep this in mind the next time we aim our cannons at a target, which in other words might be called human beings.

What choice did I have when I set out to write but to become one of the Absurdelekh? In a world like this, who can say that precious logic and reason must rule the page? Why must the magician always be pulling rabbits out of hats? For once let the hat emerge from the rabbit. Or better yet, let the rabbit wear the hat and make the decisions.[TM was referring here to his story “The Magic Backwards,” published in 1926. It was the subject of fierce criticism from the Yiddish literati, who accused him of charlatanism and nihilism, among other delicate epithets. Ed.] Surely we couldn’t be worse off?

I should only like to add that this Chambermaid Prize belongs not just to me, but to all of the Absurdelekh. As humans, as men and women, as Yiddish writers, we ask the same question as Job: How can an innocent man be punished? And beyond that, in such crazy crazy ways? Avromele Katz, Pesakh Streimel, Miriam Hutgebrakht, Nokhem Shtetlboim and Anna Markowitz share this honor with me. We are a community of men and women who die and rot and stink at the end of a long dark hallway but at least we can hold each other’s noses.

A sheynem dank.